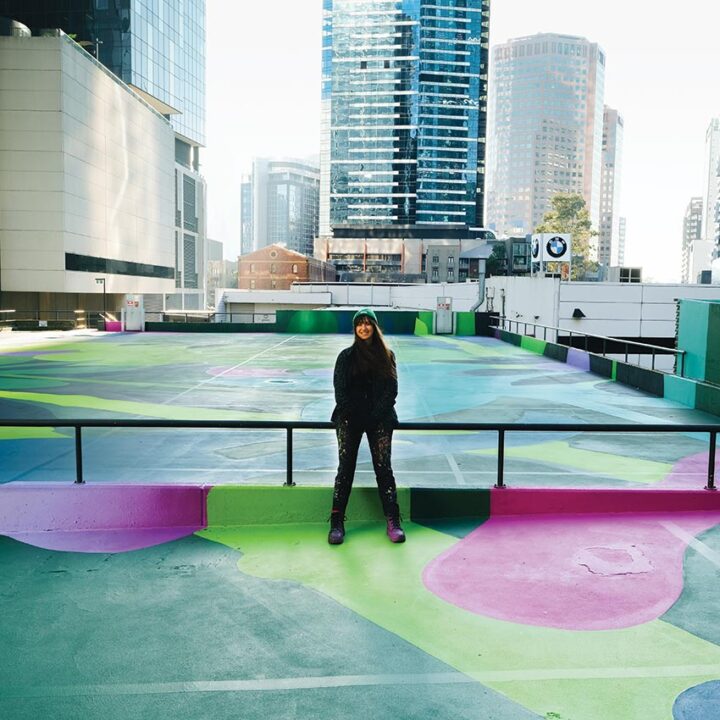

I know it can be seen as just an exciting, bright thing to bring people into a space, but for me it feels like a collaborative artwork made with so much intention. It felt this really positive encouraging offering, especially during lockdown when the city was going through so much, that was free and able to be experienced by everybody. It was like “Here’s a gift from us, we put a lot of heart into it and hope you like it”.

What does the future of art look like to you?

I think a lot about the relevance of art, especially in these trying times, and it can sometimes feel less significant or important than life-saving things. But as someone whose life has been intensely improved by not even just making it, but being surrounded by art, I think there’s so much potential for it to really define a culture and a community, literally and philosophically.

The future of art that I want to work towards is one that does not rely on the status quo to determine what should be shown. There’s so much potential in art to be groundbreaking and earth-shattering, not just visually, but in terms of who is creating the work, who is given opportunities, who is uplifted. I like the idea of art as a collaborative community-based thing that is about gift-giving and contribution, but also art as something that can speak about one person’s personal story while reflecting upon a larger community history.

I hope that we work towards a future where that potential is on earth, and not just sitting there dormant. Having worked collaboratively on Outdoor Living and seen people who put a lot of care, effort and love into something, it makes me feel as though perhaps that is an avenue that art can explore further. As someone who’s had tons of awesome artistic opportunities, it never quite feels as generous to the community when it’s just something I’ve done on my own, versus when I’ve worked with other people or allowed other voices to contribute. Art can do so more than just look good.